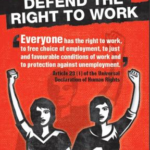

Article 23: Right to Work

UDHR Article 23

1. Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and

favourable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment.

2. Everyone, without any discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal

work.

3. Everyone who works has the right to just and favourable remuneration

ensuring for himself and his family an existence worthy of human dignity,

and supplemented, if necessary, by other means of social protection.

4. Everyone has the right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of

his interests.

As First Lady of the United States, Eleanor Roosevelt told striking workers in 1941 that she had always “felt it was important that everyone who was a worker join a labour organization, because the ideals of the organized labour movement are high ideals.”

Five years later, when she headed the United Nations committee drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), she gave international labour organisations an important role in shaping the Declaration to reflect their vision of how the world should develop.

The American Federation of Labour had a full-time staff person at the UN while the UDHR was being drafted – Toni Sender, a politician and journalist who had fled Nazi Germany. Along with other labour representatives, she argued forcefully for the specific inclusion of trade union rights. Roosevelt also helped ensure that

Article 23 spelled out, in four paragraphs, the right of “everyone” to work, with equal pay for equal work, and without discrimination. The right to form and join trade unions is also clearly enunciated.

“I belong to the generation of workers who, born in the villages and hamlets of rural Poland, had the opportunity to acquire education and find employment in industry, becoming… conscious of their rights and importance in society.”

–Lech Walesa, head of the Solidarity trade union and subsequently President of Poland

In its third paragraph, Article 23 calls for “just and favourable remuneration” to ensure “an existence worthy of human dignity” for workers and their families, reflecting again a vision of a better world than the just-defeated Nazi Germany with its slave labour.

The drafters built on the work of the International Labour Organisation (ILO), one of the few institutions from the League of Nations to become incorporated into the United Nations, when it was created in 1945. Just as the UN was founded in the wake of the Second World War, the ILO had been set up in 1919 out of the ashes of the First World War. It pursued the vision that universal, lasting peace can be established only if it is based on social justice.

Latin American delegates, along with those from the Communist bloc (whose ideology espoused full employment), were instrumental in formulating the final text of Article 23. The Soviet Union, in particular, wanted not only the final terminology of “protection against unemployment,” but greater obligations on states to prevent unemployment.

Over the past 25 years, the number of workers living in extreme poverty has declined dramatically, but unemployment is still a major issue, with more than 204 million people unemployed around the world in 2015.

Equal pay for equal work is still a dream in most countries. More generally, women face enduring obstacles in achieving economic empowerment. According to the World Bank, about 155 countries have at least one law that limits women’s economic opportunities, while 100 states place restrictions on the types of jobs women can do. In 18 states, husbands can dictate whether their wives can work at all.

Child labour also still exists in many countries. The ILO says 152 million children are engaged in mentally, physically or socially dangerous work that prevents them from getting an education. In Africa, one in five children is a child labourer, with smaller proportions in other parts of the world. Globally, around half of the victims of child labour are between five and 11 years old.

One of the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is devoted to decent work and economic growth. The UN hopes to eradicate forced labour, slavery and human trafficking, and achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men by 2030.

Unfortunately, by many measures, the world is slipping back, not progressing, in protecting workers’ rights. The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) promotes and defends workers’ rights. In its 2018 Global Rights Index, it says an increasing number of countries are chipping away at labour protection and persecuting advocates for workers’ rights in an effort to undermine trade unions and create a climate of intimidation among workers and unions.

In 2018, it reported, governments in three of the world’s most populous countries – China, Indonesia and Brazil – passed laws that denied workers freedom of association, restricted free speech and used the military to suppress labour disputes.

While workers have the right, on paper, to freedom of association, in 2018, 92 out of 142 countries surveyed by the ITUC excluded certain categories of workers (for example, part-time employees) from this right. At the same time, many consumers, largely as a result of sustained advocacy by civil society organizations, are becoming more aware of the issues covered in Article 23, such as being paid a living wage and working in safe conditions.

In addition to States, all companies, whatever their size or sector, have a responsibility to respect core labor rights such as the right to work, and the right to freedom of association and collective bargaining. This responsibility applies across a company’s global value chain and follows from the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations in 2011.

“There is no longer a choice for business to act responsibly.”

– John Ruggie, author of UN Guiding Principles on Business & Human Rights

UN Human Rights Chief Michelle Bachelet argues that there is a “colossal” cost to violations of economic and social rights. Excluding people with disabilities from the work force, for example, can cost economies as much as seven percent of GDP.

“Evidence from many business sectors indicates that respecting human rights can have a direct impact on a company’s bottom line,” she says. Consumers also have a role to play in examining the “human rights issues related to the goods they buy and the services they pay for.”

Source: United Nations’ Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

Tags: economic justice, gender justice